By Phil Ellenbecker

During the Kansas City Royals' first year of existence, a fair number of all-time greats, future Hall of Famers, came through Municipal Stadium, giving Kansas City fans a look at excellence even if their own team was a little bit lacking in it.

During the Kansas City Royals' first year of existence, a fair number of all-time greats, future Hall of Famers, came through Municipal Stadium, giving Kansas City fans a look at excellence even if their own team was a little bit lacking in it.

We're talking about players such as Frank Robinson, Reggie Jackson, Carl Yastrzemski, a few others.

The Minnesota Twins brought in future Cooperstown enshrinees Harmon Killebrew and Rod Carew for a Sunday doubleheader June 29. And that day a player many think should be in the Hall of Fame but isn't probably gave the most Hall-worthy performance a player had at Municipal in 1969.

We're talking Tony Oliva, who went 8-for-9 with hits in his final eight at-bats of the day as the Twins split with the Royals before 16,738 at Municipal Stadium. He went 5-for-5 with two homers, five RBIs and two runs scored as Minnesota tattooed the Royals 12-2 in the nightcap after dropping the opener 7-2. Oliva was 3-for-4 with an RBI in the first game.

Bob Oliver and Joe Foy each went 3-for-5 and Mike Fiore had a three-run homer to lead Kansas City to its win in a 13-hit attack that propped up the home faithful in the opener.

Oliva, a three-time American League batting champion, came within one hit of the record for a doubleheader set by nine players.

The 5-for-5, off four different pitchers, was the last of four five-hit games Oliva had in his career. The two homers in the second game were one short of his career high for a game, as were his five RBIs. He had four six-RBI games in his career and three with five. He had 17 two-homer games, one with the three.

Always a great all-around hitter for power and average, he put on a display across the batting spectrum in the nightcap with two homers to right field, a double to center, a single to center and a bunt single.

Batting out of the No. 2 slot for one of only nine times on the season, Oliva laid one down for his first hit two batters into the game. He then went deep the next inning for a three-run homer off Dave Wickersham, who'd just relieved Don O'Riley, who three batters before had relieved K.C. starter Jim Rooker. Oliva's dinger capped a six-run inning and gave Minnesota a 7-2 lead.

(O'Riley is a Royals pitcher I don't recall at all. A Topeka, Kansas, native, he pitched 28 games in 1969-70 for K.C. and had a 1-1 record with a 6.17 ERA. Guess that's maybe why I don't remember him.)

Oliva added a two-run shot in the sixth inning off Dick Drago, the fifth of six Royals pitchers, to hike the lead to 9-2. It was the 12th of 24 homers he had on the season.

Two innings before Oliva had doubled off Mike Hedlund, but he was put out while trying to advance on Harmon Killebrew's grounder back to the mound, the play going pitcher-to third-to second.

That was about the only thing that kept Oliva from a perfect game. He singled in the eighth inning off Tom Burgmeier, than gave way to pinch runner Charlie Manuel.

Also swinging big bats for the Twins were Cesar Tovar, 3-for-5 with three RBIs and three runs scored; Frank Quilici, 3-for-4 with two runs scored and a walk; George Mitterwald with a two-run homer that capped the scoring in the eighth; and Leo Cardenas, 2-for-3. (Quilici tied his game career high for hits, set four other times.)

Rooker fell to 0-5 as he was plagued by four walks in his stint that ended with consecutive bases on balls to start the second inning. Rooker had 73 walks on the year, second to Bill Butler's team-leading 91, and next year was third in the American League in walks with 102.

Hedlund was the only K.C. pitcher who had any success, throwing three scoreless innings.

Buck Martinez was the lone bright spot in the Royals offense, going 3-for-4. He actually gave the Royals a 2-1 lead in the first when he singled in Oliver.

Jim Kaat buckled down after that for the Twins and finished with a seven-hitter, the Royals getting only two runners into scoring position after the first. He improved to 8-6.

|

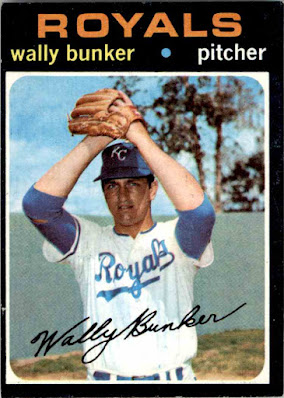

| Wally Bunker worked around 11 hits as he pitched the Kansas City Royals to a 7-2 victory over Minnesota in the opening game of a doubleheader June 29, 1969. |

Wally Bunker, who qualified as the Royals ace this year with a 12-11 record and 3.23 ERA, got the first-game win, scattering 11 hits and walking none as he went the distance. He evened his record at 4-4. A reclamation project from Baltimore, he'd pitched a six-hit shutout in the 1966 World Series but had mustered only five victories the previous two seasons as arm miseries set in.

Fiore's three-run first-inning homer off Jim Perry gave Bunker all the runs he needed. It was the seventh homer of the year for Fiore, a rookie who would finish 1969 with 12 homers and then hit one more homer in his four-year career.

Oliver left the yard for a two-run homer in the sixth off Jerry Crider, giving the Royals a 6-1 lead. It was Oliver's eighth homer. He'd finish the year with 13, one behind team leader Ed Kirkpatrick, then slug a career-high 27 next year, K.C.'s best in a season until John Mayberry hit 34 in 1975.

Besides Foy and Oliver, others with multiple hits for the Royals were 1969 AL Rookie of the Year Lou Piniella and Jackie Hernandez, each 2-for-4.

Oliva broke up Bunker's shutout with a run-scoring single in the fourth, then singled his final two times up. Bunker got him out for the only time of the day on a fly to left in the first.

While Oliva was a wrecking crew, the Royals kept the damage to a minimum from the Twins' Hall of Famers. Killebrew and Carew each went 0-for-4 in this game. The Killer, who would become this year's AL MVP, also went 0-for-4 in the nightcap. Carew, who would win the first of seven batting titles this year with a .332 average, sat out the second game.

|

| Bob Oliver went 3-for-5 and smacked a two-run homer to help the Kansas City Royals beat Minnesota 7-2 in the opening game of a doubleheader June 29, 1969. |

Perry's record dropped to 6-4 after he gave up eight hits and four runs, all earned, in 3 1/3 innings. He went on to finish the year 20-6 and then win the AL Cy Young after going 24-12 in 1970.

With stalwarts such as Perry, Killebrew, Carew, Oliva and others, the Twins won the AL West title in this first year of divisional play with a 97-65 record, nine games over former Kansas City tenant the Athletics of Oakland. Minnesota was then swept for the first of two straight years in the AL Championship Series by Baltimore.

Kansas City finished its inaugural Royals season at 69-93, which was good for fourth place in the West. Two years later they'd finish second in a prelude to success that saw them win division titles from 1976 through 1978.

As for Oliva, he went on to finish third in AL batting in 1969 with a .309 average, then added his third hitting crown and a slugging average title next year.

Probably only a pair of debilitating knees that required seven surgeries kept Oliva from a Hall of Fame career, and his numbers still rank with many already in. As it is, and with the help of the advent of the designated hitter in 1972, Oliva lasted 15 years and had a .304 lifetime average. Besides the three batting titles, he led the league five times in hits, four times in doubles and once each in slugging and total bases. He was an eight-time All-Star, one-time Gold Glove winner and Rookie of the Year.

And he was about as good as you could get on June 29, 1969.

Sources:

First game box score, play-by-play: https://www.

Second game box score, play-by-play:

https://www.retrosheet.org/

Most hits in a doubleheader: https://www.mlb.